Week 4 Lab: Crash Course Mythology

The analogy of mythology being a "slurpee of knowledge" is really good. It takes a bunch of different educational principles, religion, history, etc. and casts them into a story that tries to explain them. My understanding of a "myth" is something that is untrue, but to many peoples and cultures, they are truth, used to explain phenomena that they had no understanding of in the past. I appreciate them touching upon this, the Greek background of the word, and how he actually defined the word: stories that have significance and staying power. Consequently, mythology is the study of these myths.

Concerning mythology, this dates back to ancient Greece and the Greek philosophers, where there was contention regarding attributing human attributes to the gods, especially the negative ones. With many denoting myths as lies, a dichotomy was able to be setup for the logos, the truth, of the Christian belief. Paul, in his Epistle to Timothy, implores his spiritual child not to give heed to "myths and endless genealogies, which promote speculations rather than the stewardship from God that is by faith" (1 Tim. 1:4, ESV). My view of myths is similar to Frazer's; myths are a primitive placeholder for scientific discovery. As technology progresses, myths are eventually displaced. Of course, as humanity and philosophy continue advancing as well, more theories of the place of myths in society are generated as well.

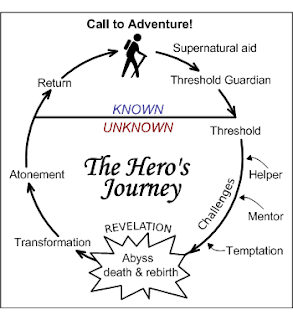

The breakdown of the Hero's Journey, from Campbell, was useful in seeing the start of mythological heroes, and when the Ramayana for example, is viewed with these "glasses" on, we can see that framework. He believes that all hero myths share a common structure with 3 main parts: a hero separates himself from the world, usually getting some kind of call (Rama going into exile, but the gods are happy because it was destined for Ravana to be defeated); the trials/victories of initiation, where the hero overcomes to demonstrate his worthiness and obtaining some kind of prize (Rama defeating rakshasis and eventually Ravana, the king, eventually winning back Sita); and finally the return to society (this is pretty self-explanatory).

It's interesting to use this as a tool for comparing different mythological stories.

Concerning mythology, this dates back to ancient Greece and the Greek philosophers, where there was contention regarding attributing human attributes to the gods, especially the negative ones. With many denoting myths as lies, a dichotomy was able to be setup for the logos, the truth, of the Christian belief. Paul, in his Epistle to Timothy, implores his spiritual child not to give heed to "myths and endless genealogies, which promote speculations rather than the stewardship from God that is by faith" (1 Tim. 1:4, ESV). My view of myths is similar to Frazer's; myths are a primitive placeholder for scientific discovery. As technology progresses, myths are eventually displaced. Of course, as humanity and philosophy continue advancing as well, more theories of the place of myths in society are generated as well.

(The Hero's Journey, from TVTropes)

The breakdown of the Hero's Journey, from Campbell, was useful in seeing the start of mythological heroes, and when the Ramayana for example, is viewed with these "glasses" on, we can see that framework. He believes that all hero myths share a common structure with 3 main parts: a hero separates himself from the world, usually getting some kind of call (Rama going into exile, but the gods are happy because it was destined for Ravana to be defeated); the trials/victories of initiation, where the hero overcomes to demonstrate his worthiness and obtaining some kind of prize (Rama defeating rakshasis and eventually Ravana, the king, eventually winning back Sita); and finally the return to society (this is pretty self-explanatory).

It's interesting to use this as a tool for comparing different mythological stories.

Comments

Post a Comment